Aspartame is one of the most widely used artificial sweeteners in the world—and also one of the most debated. Found in diet sodas, sugar-free foods, chewing gum, and low-calorie products, it promises sweetness without calories. Yet questions about its safety, metabolism, and long-term health effects continue to surface.

This article provides a complete, evidence-based explanation of aspartame. Whether you are a casual consumer, someone managing weight or blood sugar, or simply curious about food additives, this guide explains what aspartame is, how it works in the body, why it’s controversial, and what science actually shows.

What Is Aspartame?

Aspartame is a low-calorie artificial sweetener made from two amino acids: phenylalanine and aspartic acid. It delivers intense sweetness—about 200 times sweeter than sugar—without providing significant calories or raising blood glucose levels.

Unlike sugar, aspartame is not a carbohydrate. It is a synthetic dipeptide sweetener, meaning it consists of two linked amino acids plus a small methanol component released during digestion. Because only tiny amounts are needed to sweeten food, its caloric contribution is negligible.

Aspartame belongs to the category of non-nutritive sweeteners, also known as low-calorie or artificial sweeteners.

The Chemical Structure and Sweetness Mechanism

Aspartame’s sweetness comes from how it interacts with sweet taste receptors (T1R2 and T1R3) on the tongue. These receptors respond to sweetness intensity rather than caloric content.

Why Aspartame Tastes Sweet Without Sugar

- It activates sweet taste receptors more strongly than sucrose

- It does not contain glucose or fructose

- It triggers sensory sweetness without delivering energy

This separation between sweetness and calories is central to both its benefits and its controversies.

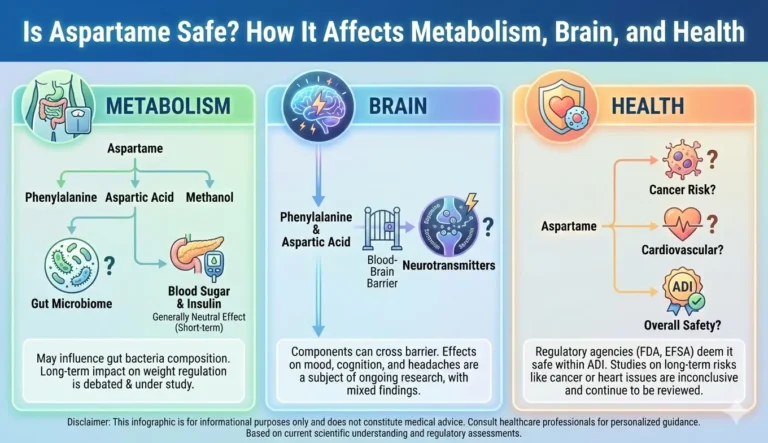

How Aspartame Is Metabolized in the Body

Once consumed, aspartame does not remain intact. It is broken down during digestion into three components:

- Phenylalanine

- Aspartic acid

- Methanol

Each component follows a known metabolic pathway.

Phenylalanine Metabolism

Phenylalanine is an essential amino acid found naturally in protein-rich foods like meat, eggs, and dairy. In most people, it is safely metabolized and used for:

- Neurotransmitter synthesis

- Protein building

- Hormonal signaling

However, people with phenylketonuria (PKU) lack the enzyme needed to process phenylalanine properly. This is why aspartame carries a mandatory PKU warning label.

Aspartic Acid and Neurotransmission

Aspartic acid is a non-essential amino acid involved in:

- Energy metabolism

- Neurochemical signaling

- Amino acid synthesis

In the brain, it functions as an excitatory neurotransmitter, but the amounts derived from aspartame are typically lower than those from normal dietary protein intake.

Methanol Conversion Pathway

Methanol released from aspartame is converted in the body through a well-established pathway:

- Methanol → Formaldehyde → Formic acid

This sounds alarming, but dose matters. The methanol produced from aspartame is significantly lower than that found naturally in fruits, vegetables, and fruit juices.

Does Aspartame Affect the Brain?

One common concern is whether aspartame or its breakdown products cross the blood-brain barrier.

Amino Acid Transport and the Brain

Phenylalanine and aspartic acid use competitive amino acid transport systems to enter the brain. In healthy individuals, these systems regulate balance tightly.

Current evidence shows:

- Normal dietary intake does not overwhelm transport mechanisms

- No consistent evidence of neurotoxicity at approved intake levels

- Individual sensitivity may vary

Claims linking aspartame to neurological disorders remain controversial and are not supported by high-quality, consistent clinical evidence.

Aspartame and Insulin Response

Aspartame does not raise blood glucose, but sweetness alone can stimulate cephalic phase insulin response—a mild insulin release triggered by taste and anticipation of food.

Key Points:

- Insulin response is small and temporary

- No glucose spike occurs

- Effects vary between individuals

For people with diabetes, aspartame is often used as a sugar alternative because it avoids postprandial blood sugar rises.

Gut Microbiome and Aspartame

Emerging research explores how artificial sweeteners interact with the gut microbiome.

Some studies suggest:

- Non-nutritive sweeteners may alter gut bacteria composition

- Changes depend on dose, duration, and the individual microbiome

- Evidence is mixed and not definitive

Importantly, aspartame appears to have less microbiome disruption compared to some other artificial sweeteners, though long-term data is still evolving.

Aspartame and Appetite Regulation

One debated issue is whether aspartame affects appetite or cravings.

The Sweetness–Calorie Mismatch Theory

This theory suggests that:

- Sweet taste without calories may confuse appetite signaling

- The brain expects energy that never arrives

- This could influence hunger hormones over time

However, controlled studies show mixed results. Some people experience no appetite changes, while others report increased cravings. Individual metabolic and psychological responses play a major role.

Regulatory Safety Evaluations

Aspartame is one of the most studied food additives in history.

Key Regulatory Bodies:

- FDA (United States) – Approved as safe

- EFSA (European Food Safety Authority) – Comprehensive risk assessment

- Joint FAO/WHO Expert Committee on Food Additives (JECFA) – Established Acceptable Daily Intake

- World Health Organization (WHO) – Ongoing evaluations

- IARC – Classified as “possibly carcinogenic” based on limited evidence, not exposure risk

Also read: Does Prostavive Colibrim Really Support Prostate Health USA

Acceptable Daily Intake (ADI)

The ADI is:

- 40 mg/kg body weight per day (EU)

- 50 mg/kg body weight per day (US)

Most people consume far below these limits, even with daily diet soda intake.

Aspartame vs Sugar: A Metabolic Comparison

| Feature | Aspartame | Sugar |

|---|---|---|

| Calories | Near zero | High |

| Blood glucose impact | None | Significant |

| Insulin spike | Minimal | High |

| Tooth decay risk | None | High |

| Appetite effect | Variable | Often increases hunger |

| Metabolic load | Low | High |

Aspartame reduces caloric intake but does not provide energy, which explains why its effects differ from sugar.

Stability and Use in Food Products

Aspartame is not heat-stable, which limits its use.

Key Stability Factors:

- Breaks down at high temperatures

- Degrades over long storage

- Less stable in liquids over time

This is why it is commonly used in:

- Diet beverages

- Cold desserts

- Tabletop sweeteners

Special Populations and Risk Factors

Phenylketonuria (PKU)

People with PKU must avoid aspartame completely due to phenylalanine accumulation risks.

Children and Pregnancy

Current evidence shows no clear harm at normal intake levels, but moderation is advised, especially during pregnancy.

Individual Sensitivity

Some individuals report headaches or discomfort. While not consistently proven, personal tolerance matters.

Why Aspartame Remains Controversial

Aspartame’s controversy is fueled by:

- Misinterpretation of animal studies

- Confusion between hazard and real-world risk

- Mistrust of regulatory agencies

- Emotional response to “synthetic” ingredients

Scientific consensus evaluates dose, exposure, and biological plausibility, not isolated findings.

Real-World Exposure and Practical Use

Most aspartame intake comes from:

- Diet soft drinks

- Sugar-free chewing gum

- Low-calorie desserts

- Flavored yogurts

Cumulative exposure remains well below safety thresholds for the vast majority of consumers.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does aspartame cause cancer?

Current evidence does not show a causal link at normal consumption levels.

Is methanol from aspartame dangerous?

The amount produced is lower than that of common fruits and vegetables.

Can aspartame help with weight management?

It can reduce calorie intake, but behavior and overall diet matter more.

Does aspartame affect gut bacteria?

Possibly, but evidence is inconsistent and dose-dependent.